President Ruto’s order for Trans Mara residents to surrender illegal firearms is a necessary tactical move, but it risks being a temporary fix if it treats only the symptom—the guns—while ignoring the deep-seated economic despair, political manipulation, and cultural distortion that created the demand for them in the first place. For decades, the gun in Trans Mara has not been merely a weapon; it has been a currency of power, a tool of livelihood, and a symbol of identity in a region where the state has often been an absentee landlord or a biased referee. This blog delves into the complex root causes that must be addressed for any disarmament to be sustainable, arguing that without healing the underlying wounds, confiscated guns will simply be replaced, and peace will remain a distant mirage.

Section 1: The Economic Engine of Violence: When Rustling is a “Job”

In a region with staggering youth unemployment and limited formal opportunities, crime has become a rational economic choice for many.

From Cultural Practice to Organized Crime: Cattle rustling has morphed. It is no longer about restocking herds or paying bride price; it is a multi-million shilling, cross-border criminal industry. Guns are the essential capital equipment for this “business.”

The Protection Racket Economy: The proliferation of arms has spawned a parallel “security” industry. Communities and individuals pay militias for protection from other militias, creating a perverse, violent economy where insecurity is the product being sold.

Land as a Scarce Commodity: Underlying much of the conflict is competition for diminishing productive land. Historical grievances over land allocation, coupled with population growth and climate change, have turned pastures into battlefields. The gun becomes the final arbitrator of land disputes where legal systems are mistrusted or inaccessible.

Section 2: The Political Economy of Conflict: How Leaders Profit from Chaos

Insecurity in Trans Mara is not just a failure of governance; for some, it is a feature of the political system.

The Militia as a Political Tool: Armed groups are often mobilized, funded, or tolerated by local political actors to secure votes, intimidate opponents, or exert control over constituencies. Disarming these groups threatens a potent source of political power.

The “Security Budget” patronage: Conflict justifies the allocation of large security budgets. These funds can be a source of patronage, with contracts for “security operations” benefiting a select few. Peace would dry up this lucrative stream.

Diverting Attention from Governance Failures: Persistent insecurity serves as a convenient scapegoat for underdevelopment. Leaders can point to “banditry” as the reason for poor roads, failing schools, and lack of hospitals, deflecting blame from their own mismanagement or corruption.

Section 3: The Cultural Distortion: When a Warrior Ethos Meets an AK-47

The cultural context is critical. Traditional systems of conflict resolution have broken down, and modern weapons have grotesquely distorted cultural norms.

The Weaponization of Moranism: The proud cultural institution of the Moran (warrior) has been hijacked. Instead of protecting the community with spears, young men are now enticed into criminal gangs with promises of wealth and status gained through modern weapons. The cultural respect for the warrior is exploited for criminal ends.

Collapse of Traditional Authority: Elders and traditional councils, who once mediated disputes and controlled youth behavior, have seen their authority eroded by the raw power of the gun and the allure of quick money from crime. Their voice for peace is drowned out.

A Generation Traumatized by Violence: For youth in Trans Mara, violence has been normalized. They have grown up knowing only conflict, where the gunman is the most powerful figure in the locality. Changing this deeply ingrained mindset requires more than a weapons collection drive; it requires psychological and social healing.

Section 4: A Holistic Prescription: Disarmament Must Be Part of a “Marshall Plan”

For President Ruto’s order to lead to lasting peace, it must be the first step in a comprehensive, multi-generational strategy.

An Economic “Surrender” Package: Launch a massive public works and enterprise fund specifically for Trans Mara. Offer skills training and seed capital for former rustlers and militia members to build legitimate businesses (e.g., in livestock value addition, ecotourism, green energy).

Land Justice and Climate-Smart Agriculture: Conduct a transparent, participatory land adjudication process to resolve historical grievances. Simultaneously, invest in climate-resilient agriculture and water harvesting to increase the carrying capacity of the land and reduce competition.

De-politicize Security & Build Trust: Establish a special independent security command for the region, with officers from neutral areas, to break the link between police and local politics. Invest in community policing that rebuilds trust.

Cultural Renaissance Programs: Fund and empower youth cultural programs that redefine bravery and status away from gun ownership—towards education, sports, environmental conservation, and artistic achievement. Strengthen the role of peace-loving elders.

Conclusion: The Gun is the Leaf, Not the Root

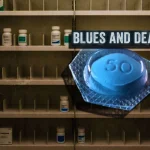

Asking Trans Mara to surrender its guns is like demanding a malaria patient stop shivering without giving them quinine. The shivering (the guns) is a symptom of the parasitic disease of economic hopelessness, political exploitation, and cultural decay.

True disarmament will not happen at the barrel of a state gun. It will happen when a young man in Trans Mara sees more power, prestige, and prosperity in a school certificate, a welding machine, or a thriving herd insured by the state than in a rusty AK-47.

President Ruto has drawn a line in the sand with the gun deadline. He must now follow it with a flood of opportunity, a tide of justice, and a renaissance of hope. Only then will the weapons be surrendered not out of fear, but out of a confident belief in a better, peaceful future.